|

Anatomy and Function

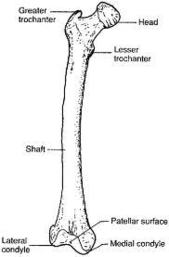

- The femur is the strongest and longest bone in the body.

- The proximal extremity consists of the head, neck, greater and lesser trenchant.

- The shaft extends from an area 5 cm distal to the lesser trenchant to 6 cm proximal to the adductor tuberecle.

- The distal extremity is comprised of the medial and lateral condyles separated by the intercondylar fossa.

- The femur approximates with the acetabulum to form the hip joint proximally and with the tibia distally forming the knee joint.

- While the vascular supply of the proximal femur is tenuous, the femoral shaft is highly vascular.

- It obtains its blood supply from nutrient vessels originating from the profunda femoris artery.

- Due to the vast blood supply, fractures heal well with little complication; however, significant hemorrhage after injury is likely.

- The proximal and mid-femur are innervated by the femoral nerve and the sciatic nerve.

- The femur transmits weight from the body to the lower extremities.

- The shaft is surrounded by several strong muscles.

- These muscles are encased in fascia creating the anterior, medial and posterior compartments of the leg.

- By understanding the muscle attachment sites, the physician can predict the displacement of the femur after fracture.

Trauma

- Femoral shaft fractures are caused by high energy trauma including motor vehicle accidents, pedestrian vs. auto, motorcycle accidents, fall from heights and gunshot wounds.

- Comminuted fractures occur more commonly from gunshot wounds and direct side impact of a motocycle accident.

- Spiral fractures are more commonly seen after fall from heights.

- Motor vehicle accidents and auto-pedestrian accidents commonly result in transverse fractures.

- 70% of femoral fractures, specifically spiral fractures, in children less than 3 yr old are secondary to nonaccidental trauma.

- Rarely, pathologic fractures of the femur occur.

- Distal femur fractures account for 4% of all femoral fractures.

- These are also related to motor vehicle accidents and significant falls.

- These fractures include the extra-articular supracondylar fractures and intra-articular fractures�the condylar, intercondylar and epiphyseal injury.

- Patients with femur fractures often present with a swollen, painful, ecchymotic and shortened thigh. They usually are unable to move the knee or the hip.

- It is important to remember that femur fractures rarely present without other associated injuries.

Classification

- There are multiple classification systems for femoral shaft fractures.

- For the ED physician, it is important to describe the location of the fracture (proximal, mid-shaft, or distal third), the geometric description (transverse, oblique, spiral, comminuted), whether it is open or closed, and whether it is displaced or angulated.

- Distal femur fractures can be divided into four types: supracondylar, intercondylar, condylar, and distal femoral epiphyseal fracture. These can be further subdivided depending if they are nondiplaced, displaced,comminuted or impacted.

Management

Prehospital Care

- The ABCs should be assessed and treated initially.

- After stabilization, a brief neurovascular exam of the extremity should be performed.

- Open wounds should be dressed with a sterile dressing.

- Bleeding should be stopped with direct pressure.

- The patient should be splinted and placed in a position of comfort.

- Traction devices such as a Hare splint may be placed as it can reduce pain and can tamponade further blood loss.

- Contraindications to traction include open fractures, suspected sciatic nerve injury, fracture of the ipsilateral pelvis or lower extremity, and fractures near the knee.

ABCs

- Femoral shaft and distal femoral fractures are associated with multisystem trauma.

- As such, the patient�s airway, breathing, and circulation is to be assessed.

- Extremity injuries can be assessed during the secondary survey.

- It should be noted that significant blood loss, up to 1.5 L, can be associated with femoral shaft fractures.

- However, studies have shown that isolated femoral neck fractures are not associated with hypotension and the ED physician should not attribute hemodynamic compromise to such a fracture.

- A search for other sites of hemorrhage is mandatory.

- Early fluid resuscitation is mandated.

Physical Exam

- Femoral shaft and distal femur fractures are obvious.

- Swelling, deformity, tenderness, and ecchymosis are common.

- In performing a physical exam, the ED physician must assess the pelvis, ipsilateral hip, knee, and lower extremity.

- Neurovascular status is essential.

- In distal femoral fractures, it is important to evaluate the popliteal artery and vein as well as the tibial and peroneal nerves.

- Although compartment syndrome in the thigh is rare, the compartment should be evaluated and pressures obtained if elevated pressure is suspected.

Radiography

- Once the patient is stable, standard plain films including AP and lateral femur should be obtained.

- In one study, 13-31% of patients with associated femoral neck fractures went undetected.

- Be vigilant for other fractures or dislocations and obtain films to rule out these injuries.

Treatment

- Once stabilized, femoral shaft fractures can be splinted with a Hare traction or Sager splint.

- If there is a contraindication to splinting (see above), then a plaster or fiberglass-reinforced bulky dressing should be substituted.

- Early adequate analgesia is essential for the patient.

- If the fracture is open, broad spectrum antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis should be administered.

- Early orthopedic consultation is critical.

Complications

- Complications in femoral shaft fractures include compartment syndrome, fat embolism syndrome, vascular injury, malunion, osteomyelitis, and myositis ossificans truamatica.

- The first four are critical for the ED physician to recognize.

- Compartment syndrome occurs in the anterior, posterior, or medial compartments of the thigh after femoral fractures, crush injury, burns, PASG, and drug use. The condition is rare due to the fact that the compartments of the femur can expand substantially. Findings include tense compartments associated with pain out of proportion with passive stretching of the muscles involved. Paresthesias, diminished pulses, pallor, and poikiothermia may also be manifested. Absent pulses are a late finding, and often the damage is irreversible. Measurement of the compartments is necessary (>0 mm Hg is abnormal, and microcirculation is compromised when pressures reach 30 mm Hg). Emergent fasciotomy is recommended for compartment syndrome. Potassium, myoglobin, CK, and renal function should be assessed

to rule out associated hyperkalemia, myoglobinuria, and rhabdomyolysis.

- Fat embolism syndrome occurs in 2-23% of patients with femur fractures. Clincial findings are fever, tachycardia, respiratory distress, altered mental status and, although a late finding, a petechial rash over the chest. Management includes supportive care with vigilant airway management.

- Vascular injury primarily occurs with penetrating trauma (GSW) although it can be associated with fractures and dislocations. Signs of vascular injury include pulsatile hematoma, hemorrhage, absent distal pulses, palpable thrill or audible bruit.

More often than not, patients with penetrating trauma do not illicit these �hard� findings and have more subtle findings such a small nonexpanding hematoma, diminished pulses etc. Modrall, Weaver, and Yellin�s algorithm for penetrating trauma is shown on Figure 8.2. If a patient has signs of vascular injury, then arteriogram

and surgical repair is necessary. If soft signs are present, or the ABI is < 1.00 arteriography is warranted. If the ABI is =1.00 observation is recommended.

|

|

|

Total QuestionsWe have 1032 questions.

|